Close contact quarantines were a disaster for children

Detroit was quarantining over 400 students a week in October 2021, according to new Chalkbeat reporting.

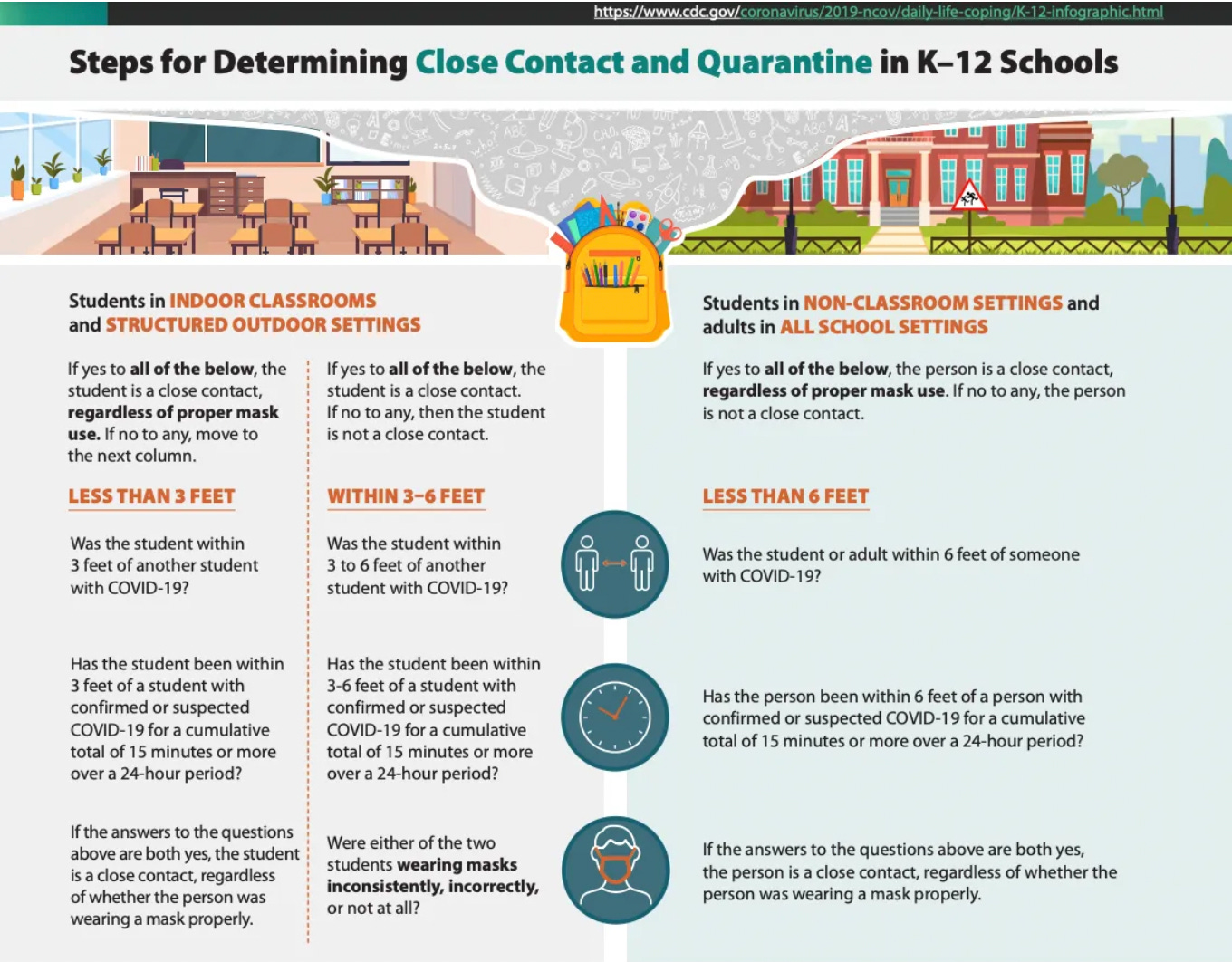

Chalkbeat Detroit just published a fascinating piece about chronic absenteeism in the city’s school system, which noted that “easing of COVID safety protocols helped the Detroit school district record a significant decrease in its chronic absenteeism rate this past school year.” By “COVID safety protocols,” the piece is mostly referring to the close contact quarantines that required unvaccinated children — and that was the vast majority of U.S. children in 2021 — exposed to someone with Covid-19 to stay home from school for 10 days. It is, of course, unsurprising that chronic absenteeism declined after city schools stopped forcing healthy children to randomly stay home for almost two weeks. What is shocking, however, is just how many children were being quarantined when the policy was in force — a lot!

According to the Chalkbeat piece, “the district had more than 400 students a week in quarantine” in October 2021. To put that number in perspective, many small town high schools have 400 total students.

As education policy expert John Bailey argued earlier this year, close contact quarantines were arguably more disruptive to student learning than extended virtual instruction during the 2020-21 school year, because no live instruction was provided for children forced into quarantine by CDC guidance:

It appears that many of these students were not given live lessons with teachers during their isolation. Only four of the largest 100 districts promised live instruction for quarantined students, and just 36% of quarantined students reported having live classes with teachers. In Los Angeles, parents reported their quarantined children were sent home with just paper work packets or no assignments at all — an experience that was all too common in other regions.

And, of course, it wasn’t just loss of instructional time that quarantined children faced when locked out of school. They were more likely to be exposed to gun violence, lost access to nutritional meals, and may not have had access to the digital devices and WiFi necessary for self-study. Moreover, in some homes, particularly where parents are consumed by work or other care responsibilities, maintaining good school attendance is a constant struggle — one that was unnecessarily exacerbated by forcing perfectly healthy children to leave school.

Close contact quarantines were also inequitable. Data from Northern Ireland found that they were basically useless from an epidemiological standpoint and that children from poor areas were more likely to be quarantined than children from affluent areas:

The ministers also cited a study from Public Health Scotland on the 2020/21 school year which found that only 7.9% of close contacts in primary school and 2.3% of close contacts in post primary schools went on to become cases.

"Data on close contacts collected by the PHA during spring term 2021 shows similar patterns," the ministers wrote.

"Analysis of over 18,500 school close contacts who were asked to isolate showed that the vast majority did not go on to become cases.

"PHA analysis of these 18,500 close contacts showed that children from the most disadvantaged areas were more than twice as likely to have to isolate compared to children from the most affluent areas further exacerbating inequalities."

Sweden never used close contact quarantines in schools and both Florida and much of Northern Europe ended the use of close contact quarantines in fall 2021, but because of unchanging CDC guidance, many U.S. school districts continued employing them for unvaccinated children — again, the majority of U.S. children — through the start of the 2022-23 school year.

With the news about pandemic learning loss looking bleak, it’s worth reflecting on whether less quarantining might have contributed to less chronic absenteeism and learning loss.

The hope was that, by now, students would be learning at an accelerated clip, but that did not happen over the last academic year, according to NWEA, a research organization that analyzed the results of its widely used student assessment tests taken this spring by about 3.5 million public school students in third through eighth grade.

In fact, students in most grades showed slower than average growth in math and reading, when compared with students before the pandemic. That means learning gaps created during the pandemic are not closing — if anything, the gaps may be widening.

“We are actually seeing evidence of backsliding,” said Karyn Lewis, a lead researcher on the study.

A bipartisan pandemic response commission would thoroughly assess the impact of close contact quarantines on both Covid-19 spread and student learning, but according to Philip Zelikow, who helped author an independent pandemic response report, the Biden administration is disinterested in such a project:

But the big reason, the deeper reason is because the Biden administration decided it didn’t want a commission. There were some very senior officials who were supportive. I think the view that carried the day could be summarized as: more trouble than it’s worth. … What’s our political interest in this?