Joe Biden doesn't have a universal health care plan.

This is an opportunity for Dean Phillips.

Health care costs are crushing Americans, even the insured. The reason is simple: unlike all other rich countries, the United States does not have a universal health care system. Because of this, many Americans — even the insured — aren’t protected from the crippling costs of health care or are unable to access necessary health services.

While Joe Biden takes pride in having helped to deliver the Affordable Care Act, even before Republicans gutted the individual mandate and Medicaid expansion it did not put the country on a path to true universal health care. Indeed, the ACA even has a provision where those ineligible for Medicaid, but unable to afford private health insurance on the marketplace, are spared the bite of the individual mandate. Needless to say, it’s bizarre for a policy intended to help lower-income Americans access health care to exclude lower-income Americans by design.

Over the past few years, Biden has taken some efforts to improve the ACA — for example, expanded marketplace subsidies, some regulatory action on mental health care, and other tweaks here and there — but has not fought for the public option he promised during the 2020 campaign. He also failed to articulate a policy pathway or vision to move from the ACA to universal coverage.

Given the centrality of health insurance to the financial security and welfare of Americans, this presents an opportunity for Rep. Dean Phillips (D-Mn) to draw a contrast with Biden during the upcoming primary campaign. During his campaign announcement, Phillips said:

America has no health care system -- only sick care. And that care is more expensive right here in America than it is anywhere else in the entire world.

And while speaking to Dartmouth University students last night, Phillips used language that you might expect to hear from Bernie Sanders when discussing universal health care and Medicare for All — even going so far as to attack the greed of a major corporate health insurer headquartered in his own Minnesota district.

While Phillips’ general rhetoric about health care has been excellent thus far, I want to present a rough outline for a universal health care plan that Phillips could support as part of his campaign. It would build on the ACA and not produce a universal health care system overnight, but would be a path to a reliable, rational system — yes, a real system — for Americans.

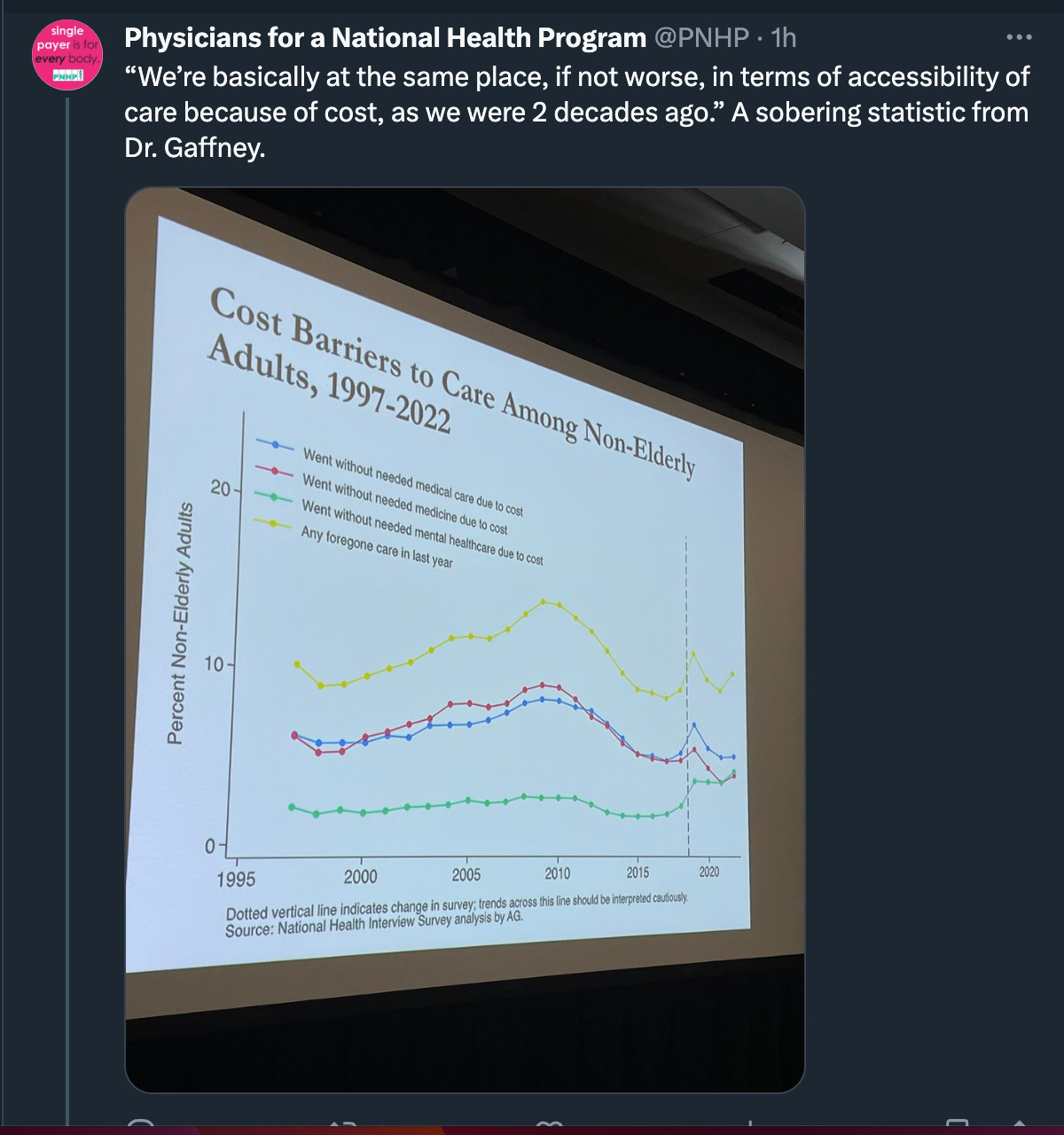

First, he would frame the push to achieve universal health care as a pillar of his broader effort to address the nation’s cost-of-living crisis and make life more affordable again for Americans. This is the only entry point, I believe, to effectively engage conservative Democrats and moderate Republicans in a serious discussion about the politically challenging issue of universalizing health care. Many Americans struggle to understand the logic of social insurance programs — especially how they put downward pressure on the costs of basic needs — and that's why it's so important to use thoughtful, purposeful language when discussing them. As the tweet below explains, the ACA has done very little to address financial barriers to accessing health care and costs remain outrageous compared to other OECD countries.

Second, Phillips would set a clear goal — eliminating medical bankruptcy in the United States by guaranteeing quality health insurance coverage to all Americans. I’ve emphasized quality, because many ACA plans aren’t “quality” plans — some have huge deductibles around $10,000 for individuals and $20,000 for families. In addition, there are coverage and access gaps resulting from narrow provider networks and incomprehensible bureaucracy. I’m spitballing here, but I think a $1,000 deductible cap for private insurance might work — in the Netherlands, which has an insurance-based health care system, the standardized annual deductible is €385. Ideally, deductibles — or any other cost-sharing like co-pays and co-insurance — wouldn’t apply to primary health care visits, chronic disease treatment, and any health care for children 18 and younger.

Third, quality insurance would be universalized by leaning into Medicaid-as-a-public-option, which is something that Phillips has supported in the past. This universalization would begin by automatically enrolling children 18 and younger into Medicaid when they present at a doctor or hospital without health insurance. This coverage would be maintained unless parents actively enrolled children into another health insurance plan. For those over 18, Medicaid would replace low-quality, high-profit “student insurance plans” at universities. And the federal government would require that Medicaid be offered as an option on the ACA exchanges. Employers would also be allowed to choose their state’s Medicaid program as their employer-sponsored insurance option. Over time, Medicaid would evolve to be seen as the public option and, because there is significantly less cost-sharing than with commercial private plans, Americans would likely be drawn to Medicaid over private plans. Ultimately, we would probably arrive at a universal health care system roughly equivalent to the German system with state Medicaid programs becoming something like German sickness funds.

If Phillips and his team have another plan, that would be fantastic, too. The goal is to present some kind of universal health care vision or political framework for dramatically expanding the quantity and quality (i.e. financial protection and access to care) of health insurance coverage — a framework that, within a decade, could bring the U.S. to near-universal health care.

Just talking about the need to achieve universal health care with clarity and specificity — demonstrating a sense of urgency about it — would be a major contrast with President Biden, inspire voters, and demonstrate a commitment to resolving one of the biggest cost-of-living pain points for Americans.